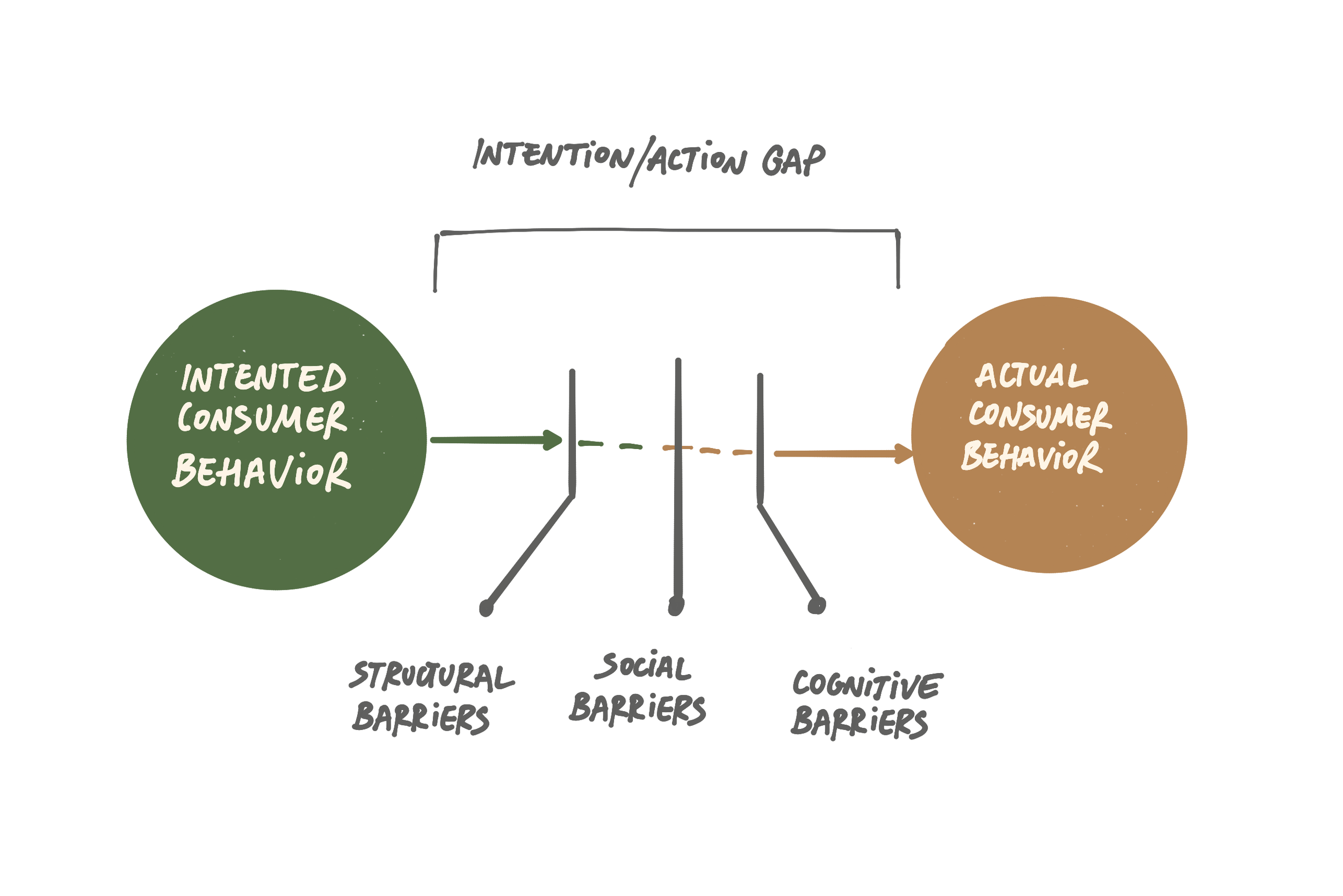

The (Sustainability) Intention-Action Gap

Consumers say sustainability considerations are important in their purchase decisions, but they do not act on that belief by making sustainable choices and engaging in pro-environmental behaviors after making a purchase.

What are people actually saying and doing? What is the disconnect between those two things that designers and marketers need to better understand if we are to try to bridge that gap?

Instant reward versus distant benefits

Given the heightened awareness and worry about ecological issues, why don't those who advocate for sustainable consumption always match their deeds with their beliefs? In 2017, a collection of public survey and trade exploration organizations performed a study from the European Commission to assess consumer interaction with the idea of an growing "circular economy". Specifically, they sought to gain further insight into how people make the decision to acquire a durable or short-living item, repair instead of replacing it, switch to a leasing/ renting system for shared items or consider buying used or renovated items.

According to them, most respondents expressed a willingness to engage in more sustainable consumer behaviors, but they had little experience with sharing businesses or buying secondhand products. Possibly due to the lack of social cachet or intrinsic rewards associated with acquiring new alternatives, such options do not convey the same sense of intrinsic rewards. Why should I pay more for a product that offer vague and distant benefits for Mother Earth whereas my go-to-brand is enough for me right now?

Evidence indicated that if consumers weren't well-informed about a product's longevity and ability to be fixed, or if sharing seemed too complicated, or if the process necessitated too much thought, they wouldn't make any effort. This is a great indication of a large difference between what people claimed they would do to engage with the circular economy and how much effort they were actually willing to put in.

Barriers to encourage green behaviours

During the spring of 2019, GlobeScan and its partner organizations, which included some of the biggest consumer brands such as Ikea, Pepsico, Procter & Gamble and Visa, conducted a survey in 25 countries to assess what keeps people from engaging in sustainable behaviour and how companies can influence it. The outcome showed that over 60% of respondents saw environmental deterioration, air pollution, climate change and plastic waste as serious problems.

There was also a significant gap between respondents' attitudes and actions regarding sustainability in this case, according to the researchers. Although over half of respondents rated living sustainably as a priority, only about a third said they were actually doing it.

Among the barriers respondents cited as preventing them from achieving a more sustainable lifestyle were personal and motivational:

inconvenience,

a lack of time,

a lack of trust in brands,

a lack of social support,

or a sense of futility.

Most frequently, however, the barriers cited were more systemic and structural-unaffordable green products and lack of government, corporate, and NGO support.

A wider gap?

The gap between consumer intentions to live a sustainable lifestyle and actual behaviors in that regard seems to be influenced by structural, social, and psychological factors. Regardless of who one might assign responsibility for bridging this intention-action gap, there are reasons to assume it may actually be a wider divide than research suggests.

We don’t seem to have much evidence that changes in consumer attitudes are leading to proportional changes in environmental behavior. As far as we can tell, waste continues to pile up, vehicle kilometres continue to increase, biodiversity continues to decline, and emissions continue to rise.

The better-than-average-effect (BTAE)

People often exaggerate their engagement in eco-friendly activities compared to others. For example, food waste is a worldwide problem and post-harvest loss amounts to around 30%. However, an American survey regarding consumer perception of this issue (Neff et al., 2015) showed widespread knowledge of it as well as personal effort being made. Surprisingly, most respondents claimed they wasted less than the typical individual.

According to subsequent research conducted across the US, Europe, and Asia, most people also believe that their behaviors across a variety of activities are more environmentally friendly than others. It's not uncommon for consumer research to exhibit a social-desirability response bias as part of this "better-than-average" effect in reported behavior.

Eco-consumer = regular consumer?

While many consumers appear to be knowledgeable about and concerned with the environmental effects of their behavior, there is a discrepancy between their perception and their reality. Studies show that, people who are environmentally conscious and actively aim to reduce their carbon footprint were indistinguishable from those who are less informed in terms of the magnitude of their ecological footprints.

We can perhaps explain this innocence by the lack of accurate insight into their own behaviour and the factors that influence it.

Bridging the gap?

When presented with an offering, and generally speaking, humans tend to seek least-effort solutions when trying to accomplish some goal. Instead of thinking in a slow and effortful fashion when confronted to a choice, we satisfy ourselves in relying on convenient shortcuts that trigger good-enough judgments much of the time. We make decisions about problems in a fast and efficient manner.

Now, when faced with sustainable options during our daily consumption, we often do not have the luxury of time and mental energy to study extensively every packagings on the shelves, we make purchases under stress and in the face of constant distractions. The reality is that overcoming our automatic-thinking requires strong cognitive effort and control, which has a physical cost. Combined with the financial costs of some green option may become hard to balance the trade-offs.

The cognitive, physical and financial cost to green alternatives imposes quick shortcuts of decision-making and override our best intentions.

For brands and products to attract eco-friendly behaviour, it is good-practice to tap into existing network of associations in the brain: colours associated with sustainability, natural textures and materials, and most importantly concrete numbers on past and/or present benefits of the particular green-alternative we are offering.

What are your ways of bridging the gap?