Mindful Product Design Development: How Six Eco-Design Approaches Create Sustainable Products

We live in an economic system that has progressively altered the relationship between human resources and material energy. At the same time, the impact of industrial production on the planet's ecosystem continues to increase exponentially. In light of the environmental problems resulting from growth and development, it has become necessary to rethink our concepts of growth and development.

Although this reassessment began in the early 1960s and took on a global perspective, particularly with The Limits to Growth by D. H. Meadows, D. L. Meadows, J. Randers, and W. W. Behrens published in 1972, it has only been since the 1990s that close ties have been established between environmental themes and industrial production, after political and regulatory discussions in the 1980s.

We have since learned that considering the environmental impact of a product once it enters the market cannot simply be ignored anymore. It means incorporating production processes, the products themselves, and the behaviors they trigger within the limits of ecological sustainability. A product's performance cannot be limited to functionality and aesthetics alone as it used to a couple of decades ago.

Sustainable design means considering all aspects of an object's function, so that, we, designers, not only shape its form but also influence production methods and consumer behaviors in the name of greater environmental sustainability. Savings in energy, materials, packaging and transport, in addition to problems tied to disposal, are all issues that make up the fundamental structure of sustainable design. Actually, sustainable design is characterized by a dynamic creative process that seeks out innovative solutions through alternative systems, technologies, and production strategies. Unlike conventional industrial production, sustainable design takes into account the entire lifespan of a product - its intended use, market, costs, and feasibility - to achieve desired results. The shape of an object is then optimized based on functionality AND sustainability, in line with the principle of "form follows function." This approach results in products that are adaptable, durable, modular or multifunctional, and recyclable.

Today, we're looking at six major categories of eco-design, or sustainable design and how we try to incorporate those eco principles for our commissioned work and in-house projects.

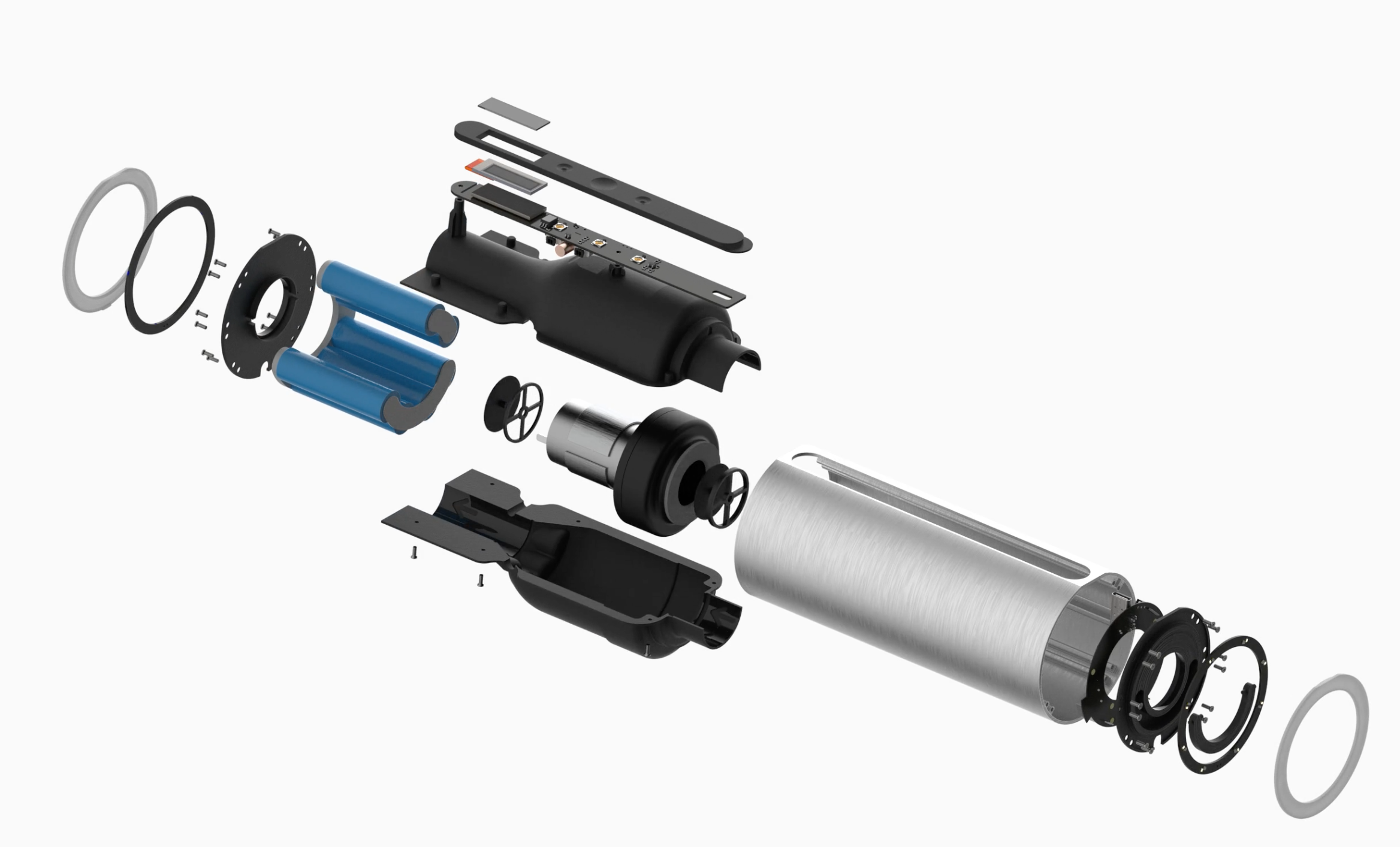

1. Design for Components

The goal of designing for components is to identify and optimize the external form of an object, starting with its size and the arrangement of its parts, or components. Each of these is considered as a finished product with an autonomous life cycle, though still in relation to the other parts.

The design starts with the analysis of disassembled objects of the same type, taking into account the relationships between components, the physical-mechanical laws that distinguish them and the technologies of manufacturing.

Once the single parts are defined, the key elements that make the object work are identified, and the creative phase begins, at which point the designer works according to the following guidelines: combining components of the same material and avoiding the use of different materials; marking the materials permanently (with stamps or labels); minimizing waste production; pre-determining any breakage points to facilitate rapid removal of parts; avoiding forms and systems that could complicate disassembly.

Designing for components also means taking into account the accessibility of the product in terms of making it easy to use and maintain.

2. The Sustainable Lightness of the material

An analysis of the products on the market shows that there is a general tendency towards redundancy in the use of materials. Designing according to the logic of reducing materials means optimizing the amount of both materials and energy in the development of a product. Such reductions have a double advantage, helping to both protect resources and decrease harmful emissions.

In taking this approach, we, designers, should also avoid using different materials, since this complicates the recycling and disposal processes.

Products created this way also satisfy the principle of design for disassembly, since an object needs to be taken apart before it can be recycled. Correspondingly, making the materials easy to recognize is important, since each component can be reused or recycled even when made of different materials. For this reason, many countries have launched regulations that require the marking of objects and components for fast identification.

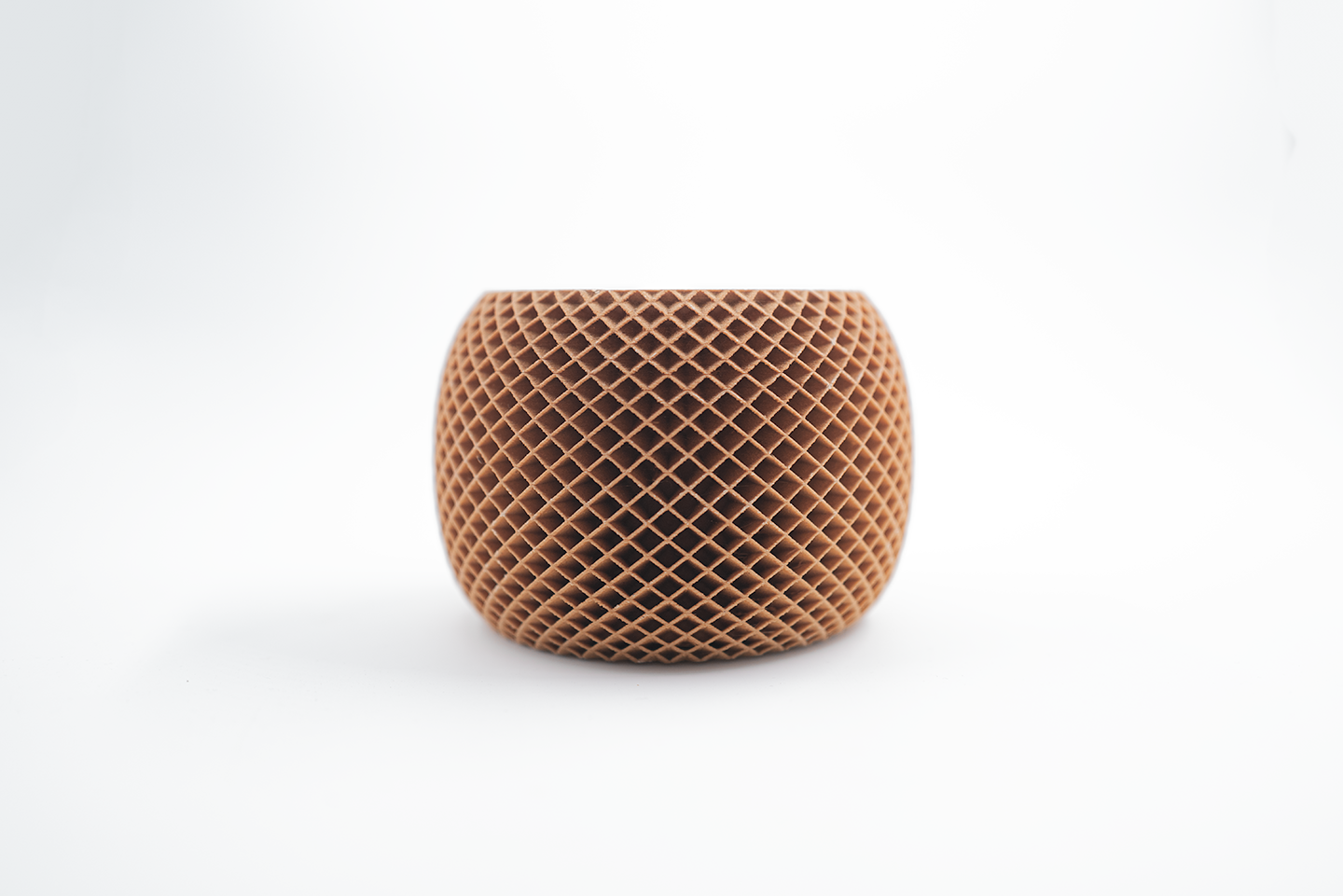

3. Use of Mono & Bio-Based Materials

Despite how easy it is to apply, the sustainable design principle of using just one material is often neglected. Unfortunately, the request for product appeal often prevails over environmental issues, resulting in the increased spread of high-impact products. Designing in a sustainable way, however, means using the most suitable resources for an object and its function, not just satisfying the laws of the market.

There are many advantages to using only one material since designing this way means simplifying both the initial manufacturing and the final recycling processes. This approach generally applies to relatively simple products, disposable objects and the single components of more articulated products.

Considering the environmental costs of extraction, transformation and disposal of resources, sustainable design also generally involves the use of "bio-based" materials. These include both organic materials and the derivatives of natural products, such as biodegradable non-oil plastics, produced for example with cornstarch or potato starch (PLA).

4. Multi-use Materials & Reparability

Though similar, the concepts of recycling and reuse differentiate themselves in the products they generate. Whilst recycling involves the transformation and reuse of the material or materials of the object being recycled, reuse puts the object itself back to work, involving purely formal and structural, rather than chemical or physical, changes when it comes to life span, whereas in the second case, it is the object itself that endures.

Recycling includes numerous sub-categories, the best known of which are cascade, post-consumer and pre-consumer recycling.

The first involves the recovery of materials for increasingly simplified uses with respect to their original one; this is due to the loss in structural and chemical quality involved in their transformation.

Post-consumer recycling, the most well-known, involves the transformation of materials or parts of a product at the end of its life, following separated waste collection. More theoretical and less well-known is pre-consumer recycling. Here the actual need to put the product on the market is checked at the start. If the results are unsatisfactory, pre-recycling takes place, that is, production is suspended, thereby avoiding the waste of resources beforehand.

5. Size Reduction & Logistics Optimisation

Compressing, reducing, and limiting consumption during transport: these are the requirements an eco-designer must keep in mind when developing an idea for a new object. Saving materials is only part of it; the intelligent design of a product's dimensions also means preventing excessive consumption by the vehicles used for its transportation. The more products carried on a single trip, the less aggravating are the CO2 emissions on the environment. Immediate benefits are also felt in terms of fuel savings.

Size reduction follows two main guidelines:

designing both product and packaging at the same time;

providing for assembly following purchase.

There is a close relationship between these two guidelines during the design

phase. An acknowledgment of their needs and characteristics produces a highly functional result, which is essential when it comes to the size and use of materials.

Space during the transport phase is thereby optimized and the packaging, in its turn, has to comply with the object as much as possible, both protecting it and avoiding unnecessary empty spaces. This does not however lessen the communicative strength of the packaging, whose role is also to present the product on the market in the best way.

In addition to the size and weight of the merchandise, the means of transport itself is also important. A more widespread use of alternative energy vehicles, ones that use natural fuels or renewable sources instead of fossil fuels, would contribute to a drastic reduction of a product's environmental footprint.

6. Service Design or 0% Product

Can an object be replaced with a service? The sphere of service design aims to provide an affirmative answer to this question by studying systems that offer alternatives to the individual use of an object. The response to this kind of service is generally very positive since the use of a product is generally born out of the need to facilitate an action rather than the desire to possess the object in itself.

In this approach, the offering becomes a mix of products and services, with a single owner who supplies a service to several users. The owner profits financially by minimizing resource consumption, emissions and waste, and therefore aims to look after the product for its duration.

This is the case with car-sharing. A service like this, which puts a car owner in touch with someone who needs a ride, satisfies the needs of a group with a single vehicle, reducing the costs of both owning a car, on the one hand and traveling, on the other. It also stimulates users to develop conscious and sustainable habits, since car trips are reduced to strict necessity, and it fosters new relationships between people, places and objects.

7. Techno-cologic

An object can be made eco-compatible through the use of the appropriate technology. We might think, for instance, of the technological opportunities for improving the efficiency of products, promoting energy savings and combining several functions in one object, not to mention nanotechnology and biotechnology. While industrial production remains strongly tied to the exploitation of materials and resources, despite well-founded accusations of excessive use and consequent pollution, sustainable technological development operates increasingly towards saving materials, which also boosts the spread of the services.

Moreover, technologies with a low environmental impact are becoming increasingly widespread. Unlike conventional design, sustainable design moves within a rich imagination of qualities and values, in which communication between products and systems is open and reciprocal. Creative solutions thus take shape at the technological avant-garde, with ecological sustainability as their goal.

8. Saying, Doing, Sustaining

While the usual means of communication are used to express and spread environmental sustainability, eco-advertising exists on several levels and takes various forms. In fact, messages about environmental issues reach the public through more than just the media and focused promotional campaigns, which use graphics and slogans as their immediate tools of expression; there is always a new product on the market that declares its sustainability in one way or another, making it the strength of the company. Sometimes these products convey the message directly by integrating it as part of their design.

Others carry environmental certifications born of meticulous and complex procedures, though these are often difficult for the consumer to read. Others call for eco-friendly behavior or propose educational games that spur kids to adopt a new point of view on the world in which we live. Sustainability can therefore be both the direct subject of the message and a tool for validating and publicizing a product on the market.

9. Zero Emissions & Circular Economy

The secret of good design is not just about showing off a product and enhancing its aesthetics. Operating within a set of social, cultural and ethical values, sustainable design must also take into account the systems and relationships within which the products are generated. It is therefore important to sketch out and plan the flow of materials from one system to another, since the impressive economic cycle thus generated gradually reduces the ecological footprint of products. This is the purpose behind systemic design: to carefully study all secondary and waste products created by the use of resources, both to obtain information and to make a genuine assessment. Production waste, for example, remains unused and is therefore a cost.

Systemic design is about devising a new production model in which industrial cycles are open and connected to one another. This way, flows of material resources (secondary products) and energy resources could be generated that both ensure all waste products are used and stabilize single systems over the long-term.